Q1. What is fixed income?

Fixed income refers to a type of investment in which an investor lends money to an issuer (usually a corporation, government, or other entity) in exchange for periodic interest payments and the return of the principal amount at a predetermined future date. Fixed income investments are also commonly known as bonds or debt securities.

Q2. What are some common types of fixed income securities?

a)

Treasury

Bonds: These are

debt securities issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury to finance

government spending. They are considered one of the safest fixed income

investments and come in various maturities, from short-term Treasury bills to

long-term Treasury bonds.

b)

Treasury

Notes: Similar to

Treasury bonds, Treasury notes are medium-term debt securities issued by the

U.S. government. They typically have maturities ranging from 2 to 10 years.

c)

Treasury

Bills (T-Bills): T-Bills

are short-term debt instruments with maturities of one year or less. They are

issued at a discount to their face value and do not pay periodic interest.

Instead, investors receive the face value at maturity, effectively earning the

difference between the purchase price and face value as interest.

d)

Municipal

Bonds (Munis): These

are debt securities issued by state and local governments, as well as their

agencies, to fund public projects such as infrastructure, schools, and

hospitals. Municipal bonds offer potential tax advantages for investors.

e)

Corporate

Bonds: Issued by

corporations to raise capital, these bonds come in various credit qualities.

Investment-grade corporate bonds have lower credit risk, while high-yield or

junk bonds have higher credit risk but offer higher yields.

f)

Mortgage-Backed

Securities (MBS): MBS

represent ownership in a pool of residential or commercial mortgages. Investors

receive payments from homeowners’ mortgage payments, and MBS can be issued by

government agencies (e.g., Ginnie Mae) or private entities (e.g., Fannie Mae,

Freddie Mac).

g)

Asset-Backed

Securities (ABS):

ABS represent ownership in pools of assets, such as auto loans, credit card

receivables, or student loans. They are structured and securitized for

investment purposes.

Q3. What are the fundamental features of fixed income bonds?

Bonds are

debt securities issued by governments, municipalities, and corporations to

raise capital. They represent a loan made by an investor to the issuer, who

promises to repay the loan with periodic interest payments and return the

principal amount at maturity. The fundamental features of bonds include:

1. Face

Value/Principal: The

face value, also known as the par value or principal amount, is the amount

borrowed by the issuer and the amount that will be repaid at maturity.

2.

Coupon Rate: The

coupon rate is the fixed or floating interest rate that the issuer agrees to

pay the bondholder as a percentage of the face value. It determines the

periodic interest payments the bondholder receives.

3.

Coupon Payments: These

are the periodic interest payments made by the issuer to the bondholder. They

are usually paid semiannually or annually, and the amount is calculated based

on the coupon rate and the face value of the bond.

4.

Maturity Date: The

maturity date is the date on which the issuer agrees to repay the face value of

the bond to the bondholder. Bonds can have short-term (less than one year),

medium-term (one to ten years), or long-term (over ten years) maturities.

5.

Yield: The yield

represents the effective rate of return on a bond and is based on the bond’s

current price, coupon rate, and time to maturity. It indicates the total return

an investor can expect to receive from the bond.

6.

Credit Rating: Bonds

are assigned credit ratings by independent rating agencies to assess their

creditworthiness. These ratings reflect the issuer’s ability to make interest

payments and repay the principal amount. Higher-rated bonds are considered less

risky and generally offer lower yields.

7.

Callability: Some

bonds have a call provision that allows the issuer to redeem the bond before

its maturity date, usually at a premium. This gives the issuer the option to

retire the bond early if interest rates decline, potentially saving on interest

payments.

8.

Convertibility: Convertible

bonds give the bondholder the right to convert the bond into a predetermined

number of the issuer’s common shares. This feature provides the potential for

capital appreciation if the issuer’s stock price rises.

These

fundamental features help determine the value, risk profile, and investment

potential of a bond. Investors consider these factors when assessing the

suitability of bonds for their investment portfolios.

Q4. Explain the difference between a bond’s face value, coupon rate, and yield to maturity (YTM).

The face value, coupon rate, and yield to maturity (YTM) are important concepts related to bonds that help investors understand their characteristics and potential returns. Here’s an explanation of each term and the differences between them:

Face Value (Par Value):

- Face value, also known as par value or principal value, is the nominal or initial value of a bond. It represents the amount that the issuer of the bond promises to repay to the bondholder at the bond’s maturity date.

- It is typically expressed in terms of a fixed dollar amount, such as $1,000 or $1,000,000 per bond, and it does not change over the life of the bond.

- The face value is used to calculate the periodic interest payments (coupon payments) the bondholder will receive during the bond’s term.

Coupon Rate:

- The coupon rate is the annual interest rate that the bond issuer agrees to pay to the bondholder as a percentage of the bond’s face value.

- For example, if a bond has a face value of $1,000 and a coupon rate of 5%, it will pay $50 in annual interest ($1,000 * 5%).

- The coupon payments are typically made semi-annually, but they can vary depending on the terms of the bond.

- The coupon rate remains fixed for the life of the bond, regardless of changes in market interest rates.

Yield to Maturity (YTM):

- YTM is a measure of the total return an investor can expect to earn from a bond if it is held until its maturity date, assuming all coupon payments are reinvested at the YTM.

- It represents the annualized rate of return that, when applied to the bond’s cash flows (coupon payments and the face value), would make the present value of those cash flows equal to the current market price of the bond.

Q5. What is the relationship between interest rates and bond prices?

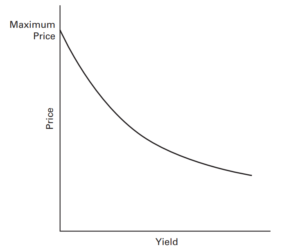

The

relationship between interest rates and bond prices is inverse and fundamental

in the world of fixed income investments. When interest rates rise, bond prices

fall, and when interest rates fall, bond prices rise.

To

understand this relationship, consider an example: Suppose you hold a bond with

a fixed coupon rate of 4% in a rising interest rate environment. If new bonds

are being issued with a 5% coupon rate, investors would prefer the new bonds

because they offer a higher return. To make your existing bond more competitive

in the market, you may need to sell it at a discount. This lower price

compensates the buyer for the lower yield compared to the newer bonds.

Conversely,

if interest rates were falling, your 4% coupon bond would become more

attractive, potentially leading to an increase in its price as investors seek

higher returns.

Q6. What are the types of risks faced by investors in fixed-income securities?

Investors in fixed-income securities face several types of risks that can impact the value and performance of their investments. Here are some of the key risks associated with investing in fixed income:

1. Interest Rate Risk: Interest rate risk refers to the potential for changes in interest rates to affect the value of fixed-income securities. When interest rates rise, bond prices generally fall, and vice versa. This risk is particularly relevant for fixed-rate bonds, as their coupon payments remain fixed, making them less attractive when market rates rise.

2. Credit Risk: Credit risk, also known as default risk, is the risk that the issuer of a bond may be unable or unwilling to make timely interest payments or repay the principal amount at maturity. Bonds issued by entities with lower credit ratings or weaker financial health typically carry higher credit risk. Credit risk can lead to a loss of income or even the loss of the principal amount invested.

3. Inflation Risk: Inflation risk refers to the potential for inflation to erode the purchasing power of future interest payments and the principal amount of fixed-income securities. If the rate of inflation exceeds the yield on the bond, the investor’s real return may be negative. Inflation-linked bonds, such as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), are designed to mitigate this risk by adjusting their principal and coupon payments with inflation.

4. Reinvestment Risk: Reinvestment risk is the risk that the cash flows generated by fixed-income securities, such as coupon payments or bond redemptions, may need to be reinvested at lower interest rates in the future. This risk is particularly relevant for bonds with a fixed coupon rate or those with call options that allow the issuer to repay the principal early.

5. Liquidity Risk: Liquidity risk refers to the potential difficulty of buying or selling a fixed-income security at a desired price and time. Less liquid bonds may have wider bid-ask spreads, meaning investors may need to accept a lower price when selling or pay a higher price when buying. Illiquid markets can limit an investor’s ability to enter or exit positions efficiently, potentially leading to increased costs or delays.

6. Currency Risk: Currency risk arises when investing in fixed-income securities denominated in a currency different from the investor’s base currency. Fluctuations in exchange rates can affect the value of the investment and the investor’s returns when converting back to their base currency. Currency risk is particularly relevant for international bonds or bonds issued by foreign entities.

7. Call and Prepayment Risk: Callable bonds and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) carry call and prepayment risk. Call risk refers to the potential for the issuer to exercise the call option and repay the bond before maturity, potentially ending the investor’s interest payments. Prepayment risk applies to MBS, where borrowers can refinance their mortgages or repay them early, leading to a different cash flow pattern for investors.

It’s important for investors to understand these risks and assess their risk tolerance and investment objectives before investing in fixed-income securities. Diversification, due diligence, and understanding the specific terms and conditions of each investment can help manage and mitigate these risks.

Q7. How to calculate the price of a fixed income bond?

The price of a bond can be calculated using the present value of its future cash flows. The formula for calculating the price of a bond is as follows:

Price = (C1 / (1+r)^1) + (C2 / (1+r)^2) + … + (Cn / (1+r)^n) + (P / (1+r)^n)

Where:

- Price is the current market price of the bond.

- C1, C2, …, Cn represent the periodic coupon payments received at each period (usually semi-annual).

- P represents the bond’s face value or principal amount.

- r is the required yield or discount rate per period.

- n is the total number of periods until the bond’s maturity.

Note: It’s important to note that the calculation assumes the bondholder will hold the bond until maturity and that all coupon payments will be reinvested at the same yield. Additionally, this calculation does not account for any transaction costs or accrued interest.

Q8. Why does the price of a bond changes in the direction opposite to the change in required yield?

The price of a bond changes in the opposite direction to the change in required yield due to the concept of bond price and yield relationship, known as the bond price-yield inverse relationship. The key reason behind this inverse relationship is the impact of changes in yield on the present value of future cash flows.

When the required yield (or market interest rate) increases, it means that investors can earn a higher return by investing in newly issued bonds or other investment opportunities available in the market. As a result, existing bonds with lower coupon rates become less attractive in comparison.

To understand why the bond price moves inversely to the yield, consider the following points:

a) Coupon Payments: Bonds typically have fixed coupon payments, meaning the bondholder receives a predetermined interest payment at regular intervals based on the bond’s coupon rate. When the required yield increases, the bond’s fixed coupon payments become less desirable compared to the higher market rates available. As a result, the bond’s price needs to decrease to offer a higher yield to match the prevailing market yield.

b) Discounting Future Cash Flows: Bonds represent a stream of future cash flows, including coupon payments and the return of the principal amount at maturity. These future cash flows are discounted back to their present value using the required yield. When the required yield increases, the discounting factor becomes larger, reducing the present value of the future cash flows and consequently lowering the bond’s price.

In summary, as the required yield increases, the bond’s price decreases to provide a higher yield to investors to align with the prevailing market conditions. This inverse relationship between bond prices and yields is fundamental to understanding bond market dynamics and helps investors assess the impact of changes in interest rates on their bond investments.

Q9. What is duration with respect to fixed income?

Duration measures the sensitivity of a bond’s or fixed income portfolio’s price to changes in interest rates.

Certain factors can affect a bond’s duration, including:

Time to maturity: The longer the maturity, the higher the duration, and the greater the interest rate risk. Consider two bonds that each yield 5% and cost $1,000, but have different maturities. A bond that matures faster—say, in one year—would repay its true cost faster than a bond that matures in 10 years. Consequently, the shorter-maturity bond would have a lower duration and less risk.

Coupon rate: A bond’s coupon rate is a key factor in calculation duration. If we have two bonds that are identical with the exception of their coupon rates, the bond with the higher coupon rate will pay back its original costs faster than the bond with a lower yield. The higher the coupon rate, the lower the duration, and the lower the interest rate risk.

Q10. What is convexity with respect to fixed income? What is the effect on positive and negative convexity on the fixed income bond?

Convexity is a risk-management tool, used to measure and manage a portfolio’s exposure to market risk. Convexity is a measure of the curvature in the relationship between bond prices and interest rate. Convexity demonstrates how the duration of a bond changes as the interest rate changes. If a bond’s duration increases as yields increase, the bond is said to have negative convexity. If a bond’s duration rises and yields fall, the bond is said to have positive convexity.

Positive Convexity:

Positive convexity means that the relationship between bond prices and yields is convex. When interest rates decline, the price of a bond with positive convexity increases more than it would decrease if interest rates rise by the same magnitude.

Negative Convexity:

Negative convexity means that the relationship between bond prices and yields is concave. When interest rates decline, the price of a bond with negative convexity increases less than it would decrease if interest rates rise by the same magnitude.

Q11. What is accrued interest and how bond prices are quoted?

Accrued interest refers to the amount of interest that has accumulated on a bond since its last interest payment date. When a bond is traded between two parties, the buyer typically pays the seller the market price of the bond plus the accrued interest. The buyer will then receive the full coupon payment on the next scheduled interest payment date.

When quoting bond prices, market participants may also use the “dirty price” or “full price,” which includes both the clean price and accrued interest. The dirty price reflects the total cost to acquire the bond, including the accrued interest up to the settlement date.

Dirty Price = Accrued Interest + Clean Price

Q12. What are the factors that affect the price volatility of a bond when yields change?

The price volatility of a bond refers to the degree of fluctuation in its price in response to changes in yields. Several factors influence the price volatility of a bond when yields change:

a) Coupon Rate: Bonds with higher coupon rates generally exhibit lower price volatility compared to bonds with lower coupon rates. This is because the higher coupon payments provide a greater cushion against changes in yields, reducing the sensitivity of the bond’s price.

b) Time to Maturity: Bonds with longer time to maturity tend to be more price sensitive to changes in yields. Longer-term bonds have a longer period over which their cash flows are discounted, making them more exposed to changes in interest rates.

c) Bond’s Credit Quality: The credit quality of a bond issuer influences price volatility. Higher-rated bonds, such as those issued by governments or strong corporate entities, generally have lower price volatility compared to lower-rated bonds. This is because higher-rated bonds are perceived as less risky and, therefore, more resilient to changes in yields.

d) Callability: Bonds with call features, such as callable or redeemable bonds, tend to have higher price volatility. Callable bonds may be subject to early redemption by the issuer, which can impact their expected cash flows and make them more sensitive to changes in yields.

e) Embedded Options: Bonds with embedded options, such as put options or convertibility features, also tend to exhibit higher price volatility. The potential exercise of these options can significantly alter the bond’s cash flows and make it more sensitive to changes in yields.

Q13. How to calculate and interpret the Macaulay duration, modified duration, and dollar duration of a bond?

Macaulay Duration provides an estimate of the weighted average time it takes to recover the initial investment in the bond. It represents the bond’s effective maturity and is measured in years. Higher Macaulay Duration implies higher price sensitivity to changes in yields.

Macaulay Duration = (C₁ * t₁ + C₂ * t₂ + … + Cn * tn + P * T) / Bond Price

Modified Duration helps estimate the approximate percentage change in bond price for a 1% change in yield. It is a useful tool for bond price risk assessment. A higher Modified Duration indicates greater price sensitivity to changes in yields.

Modified Duration = Macaulay Duration / (1 + Yield-to-Maturity)

Dollar Duration quantifies the expected dollar change in the bond’s price given a 1% change in yield. It provides a more tangible measure of the potential impact on the bond’s value in monetary terms.

Dollar Duration = Modified Duration * Bond Price

Q14. How to compute the duration of a portfolio?

To compute the duration of a portfolio and the contribution of individual securities to the portfolio duration, you can follow these steps:

a) Determine the weights: Determine the weight or proportion of each security in the portfolio. This is typically calculated by dividing the market value of each security by the total market value of the portfolio.

b) Calculate the duration of each security: Calculate the duration of each security in the portfolio using the Macaulay duration or modified duration formula for individual bonds. This can be obtained from bond characteristics or calculated using bond pricing models.

c) Calculate the weighted average duration: Multiply the duration of each security by its weight in the portfolio. Sum up these weighted durations to get the weighted average duration of the portfolio.

Weighted Average Duration = (Weight1 * Duration1) + (Weight2 * Duration2) + … + (Weight n * Duration)

Q15. What are the limitations of using duration as a measure of price volatility?

While duration is a widely used measure of price volatility for bonds, it does have certain limitations. Here are some of the limitations of using duration as a measure of price volatility.

- Assumption of a Linear Relationship: Duration assumes a linear relationship between bond prices and changes in yields. It assumes that the price-yield relationship is constant across different yield levels and changes. However, in reality, the relationship may be nonlinear, especially for bonds with embedded options or bonds subject to non-parallel shifts in the yield curve.

- Limited Scope for Non-Parallel Shifts: Duration is most effective in measuring price volatility for parallel shifts in the yield curve. It may not accurately capture the impact of non-parallel shifts, such as changes in the shape or slope of the yield curve. In such cases, more advanced measures like key rate duration or effective duration may be more appropriate.

- Ignores Credit Risk: Duration focuses solely on interest rate risk and does not account for credit risk. It assumes that the bond’s credit quality and default risk remain constant, which may not hold true for bonds with varying credit qualities or credit spreads. For bonds with significant credit risk, other credit risk measures should be considered in conjunction with duration.

- Limited Applicability for Bonds with Options: Duration does not adequately capture the price volatility of bonds with embedded options, such as callable or convertible bonds. The potential exercise of these options can significantly impact cash flows and the bond’s price sensitivity to changes in yields. Additional measures like option-adjusted duration or effective duration considering the optionality of the bond are more appropriate for such bonds.

- Not good measure for large change in yield: Duration does a good job of estimating a bond’s percentage price change for a small change in yield. However, it does not do as good a job for a large change in yield.

Q16. What is Key Rate Duration and how is it better than Duration?

Key rate duration, also known as partial duration or

bucket duration, is an extension of duration that measures the sensitivity

of a bond’s price to changes in yields at specific key points along the yield

curve. It provides a more detailed analysis of a bond’s price volatility by

capturing the impact of yield changes at different maturity points.

Here’s how key rate duration differs from duration and

why it can be considered better in certain cases:

a) Non-Parallel Shifts: Duration assumes parallel shifts in the yield curve, while key rate duration can account for non-parallel shifts. It captures the different sensitivities of a bond’s price to yield changes at different maturity points, allowing for a more accurate assessment of price volatility in scenarios with non-parallel yield curve movements.

b) Customized

Portfolio Analysis: Key rate duration allows investors to analyze

the interest rate risk of their bond portfolio in a more customized manner. By

calculating the key rate durations of individual securities in the portfolio,

investors can identify the specific maturity points that contribute most to the

portfolio’s overall interest rate risk.

Calculating the yield on a bond involves understanding the bond’s interest payments in relation to its current market price.

Calculating YTM involves solving for the interest rate in the following equation, which equates the present value of the bond’s future cash flows (interest payments and principal repayment) to its current market price:

Where:

- C is the annual interest payment (coupon payment).

- F is the face value of the bond (principal amount).

- N is the number of years until maturity.

- YTM is the yield to maturity (what we’re solving for).

Therefore, using the above equation, we can calculate the value of YTM since we have all the remaining factors (such as Market Price from Financial Market, F, C, and N)

Q18. What is the yield curve, and what are different types of the yield curve?

A yield curve is a line that plots yields, or interest rates, of bonds that have equal credit quality but differing maturity dates. The slope of the yield curve can predict future interest rate changes and economic activity. There are three main yield curve shapes: normal upward-sloping curve, inverted downward-sloping curve, and flat.

Types of Yield Curves

- Normal Yield Curve: A normal yield curve shows low yields for shorter-maturity bonds and then increases for bonds with a longer maturity, sloping upwards. This curve indicates yields on longer-term bonds continue to rise, responding to periods of economic expansion.

- Inverted Yield Curve: An inverted yield curve slopes downward, with short-term interest rates exceeding long-term rates. Such a yield curve corresponds to periods of economic recession, where investors expect yields on longer-maturity bonds to trend lower in the future.

- Flat Yield Curve: A flat yield curve reflects similar yields across all maturities, implying an uncertain economic situation. A few intermediate maturities may have slightly higher yields, which causes a slight hump to appear along the flat curve. These humps are usually for mid-term maturities, six months to two years.

Q19. How Can Investors Use the Yield Curve?

Here’s why the yield curve is important for fixed income investors:

a) Indicator of Economic Health: A normal yield curve, which slopes upwards, suggests that the economy is expected to grow steadily. Long-term bonds have higher yields as they compensate investors for the risk of holding them for a longer period. In contrast, an inverted yield curve, where short-term yields are higher than long-term yields, has historically been a predictor of economic recession.

b) Investment Strategy: The shape of the yield curve helps investors in deciding which bonds to buy. For instance, if the curve is steep, investors might prefer longer-term bonds to benefit from higher yields. Conversely, if the curve is flat or inverted, shorter-term bonds might be more attractive.

c) Risk Assessment: Different parts of the yield curve can react differently to economic changes. By analyzing these movements, investors can assess the risk level of different bond maturities and adjust their portfolios accordingly.

Q20. How do credit ratings impact fixed income investments?

Credit ratings significantly impact fixed income investments, as they provide a measure of the creditworthiness of bond issuers, whether they’re corporations, municipalities, or national governments. Here’s how they impact these investments:

a) Interest Rate and Yield: Generally, the higher the credit rating, the lower the interest rate (yield) the issuer has to offer to attract investors. This is because a high rating implies lower risk. Conversely, issuers with lower credit ratings have to offer higher yields to compensate investors for the increased risk of default.

b) Price Volatility: Bonds with lower credit ratings typically exhibit higher price volatility. This is due to the perceived higher risk of default, which makes these bonds more sensitive to changes in the economic environment, interest rates, and the issuer’s financial condition.

c) Investment Risk: Credit ratings give investors a quick way to assess the risk level of a fixed income investment. Bonds with high ratings (like AAA) are considered safer, while those with lower ratings are riskier. This helps investors in diversifying their portfolio according to their risk tolerance.

d) Liquidity: Higher-rated bonds are generally more liquid, meaning they can be bought and sold more easily in the market. This is because they are more in demand among a wider range of investors, including conservative institutional investors like pension funds.

e) Default Risk: The credit rating directly relates to the probability of default. Lower-rated bonds (like junk bonds) have a higher risk of default, meaning there’s a greater chance the issuer might fail to make interest payments or repay the principal.

f) Market Sentiment and Ratings Changes: The upgrade or downgrade of an issuer’s credit rating can significantly impact the market’s perception of that issuer, influencing bond prices. A downgrade can lead to selling pressure, while an upgrade can increase demand.

Q21. What is the difference between a government bond and a corporate bond?

Government bonds and corporate bonds are both types of fixed income securities, but they differ in several key aspects:

a) Issuer: The most fundamental difference lies in who issues them. Government bonds are issued by national governments (or sometimes subdivisions like states or municipalities) to fund government spending and obligations. Corporate bonds, on the other hand, are issued by companies to raise capital for various purposes, such as expanding operations, refinancing debt, or funding new projects.

b) Credit Risk: Government bonds, especially those issued by stable, developed countries like U.S. Treasury bonds, are generally considered to have lower credit risk compared to corporate bonds. This is because the likelihood of a government defaulting on its debt is usually lower than that of a corporation. However, this can vary depending on the specific government or corporate entity.

c) Yield: Due to the lower risk, government bonds typically offer lower yields compared to corporate bonds of similar maturity. Corporations must offer higher yields to compensate investors for the additional risk they take on.

d) Tax Treatment: The interest income from government bonds can sometimes have favorable tax treatment. For example, in the U.S., Treasury bond interest is exempt from state and local taxes. In contrast, interest from corporate bonds is generally subject to federal, state, and local taxes.

e) Liquidity: Government bonds, particularly those from major countries, tend to be more liquid than corporate bonds. This means they can be bought and sold more easily in the financial markets.

Q22. What is a callable bond, and why do issuers use them?

A callable

bond is a type of bond that gives the issuer the right, but not the obligation,

to repay the bond before its maturity date. This feature is typically set at a

specific price and after a certain date, known as the call date. Here’s a

detailed look at callable bonds and why issuers use them:

Characteristics

of Callable Bonds

Call

Feature: The most

distinguishing feature of a callable bond is the call option, which allows the

issuer to redeem the bond early. The terms of the call, including the call

price (usually at a premium to the face value) and the first call date, are

defined in the bond’s prospectus.

Coupon

Rate: Callable

bonds often have higher coupon rates compared to non-callable bonds to

compensate investors for the call risk.

Call

Premium: This is

the extra amount, above the bond’s face value, that issuers agree to pay

bondholders when calling a bond. It’s meant as compensation for the

bondholders’ loss of future interest payments.

Q23. What are some examples of callable bonds?

Callable

bonds are offered by a variety of issuers, including corporations,

municipalities, and governments. Here are some common types:

Q24. What are zero-coupon bonds, and what are their advantages and

disadvantages?

Zero-coupon

bonds are a type of bond that do not pay periodic interest payments or coupons.

Instead, they are issued at a significant discount to their face value, and the

investor receives the face value at maturity. Here’s an overview of their

advantages and disadvantages:

Advantages

of Zero-Coupon Bonds

a)

Predictable

Returns: Since

zero-coupon bonds are purchased at a discount and redeemed at face value, the

return is predetermined, making them a predictable investment.

b)

Affordability:

These bonds are

more affordable than other types of bonds because they are sold at a deep

discount to their face value, allowing investors to make a smaller initial

investment.

c)

No

Reinvestment Risk:

Unlike regular bonds, there are no periodic interest payments, so there’s no

risk associated with reinvesting those payments at potentially lower interest

rates.

Disadvantages

of Zero-Coupon Bonds

a)

Interest

Rate Risk: The

market value of zero-coupon bonds is more sensitive to changes in interest

rates compared to bonds that pay interest periodically. If interest rates rise,

the market value of zero-coupon bonds can fall significantly.

b)

No

Regular Income: Since

they do not provide periodic interest payments, they are not suitable for

investors who need regular income from their investments.

c)

Taxation: In many jurisdictions, the imputed

interest on zero-coupon bonds is taxable as income annually, even though the

investor does not receive any actual cash until maturity. This can create a tax

liability without the cash flow to cover it.

Q25. Define Credit Spreads and what is the role of credit spreads in

fixed income analysis?

A credit

spread is the difference in yield between a treasury bond and a non-treasury

bond of the same maturity. It essentially measures the additional yield that an

investor demands for taking on the additional risk of a bond with credit risk,

compared to a risk-free government bond.

a)

Risk

Assessment: Credit

spreads are a key indicator of the perceived risk of a bond. A wider spread

indicates a higher perceived risk of default by the bond issuer, whereas a

narrower spread suggests lower risk.

b)

Market

Sentiment: Changes

in credit spreads reflect shifts in market sentiment. Widening spreads can

indicate increasing concern about credit risk in the market, while narrowing

spreads can suggest increasing confidence.

c)

Sector

Analysis: Within

fixed income markets, credit spreads can vary significantly across different

sectors (corporate, municipal, mortgage-backed securities, etc.). Analysis of

these spreads can guide sector allocation in a fixed income portfolio.

d)

Investment

Strategy: For

investors, credit spreads help in making strategic decisions. For instance, in

a stable economic environment, investors might seek bonds with wider spreads to

gain higher yields. Conversely, in uncertain times, they might prefer bonds

with narrower spreads, indicating lower risk.

Q26. How do you assess the credit risk of a corporate bond issuer?

Assessing

the credit risk of a corporate bond issuer involves evaluating various

financial, business, and industry-related factors that could affect the

issuer’s ability to make interest payments and repay the bond principal at

maturity. Here’s some of the approach to this assessment:

a)

Credit

Ratings: Start

with the credit ratings assigned by agencies like Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch.

These ratings are based on thorough analyses and provide a good initial

indication of credit risk.

b)

Financial

Statements: Analyze

the issuer’s financial health through its balance sheet, income statement, and

cash flow statement. Key metrics include debt-to-equity ratio, interest

coverage ratio, profitability, and cash flow stability.

c)

Industry

Health: The

overall health and future outlook of the industry can impact the company’s

performance. Cyclical industries may pose higher risk during economic

downturns.

d)

Economic

Conditions:

General economic conditions, interest rates, and inflation trends can affect a

company’s performance and, consequently, its ability to service debt.

Q27. Explain the term “duration matching” in fixed income

portfolio management?

“Duration

matching” is a strategy used in fixed income portfolio management to

mitigate the risk of interest rate fluctuations. It involves aligning the

duration of the portfolio’s assets (such as bonds) with the duration of its

liabilities (such as obligations to pay out funds). Duration, in this context,

is a measure of the sensitivity of the price of a bond (or a portfolio of

bonds) to changes in interest rates, expressed in years.

Steps

to perform Duration Matching:

a)

Identify

Duration of Liabilities: Calculate the duration of liabilities, which is

essentially the weighted average time until liabilities are due.

b)

Align

Portfolio Duration with Liability Duration: Adjust the portfolio so that its

duration matches the duration of the liabilities. This means the portfolio is

structured so that the average time to receive cash flows from the bonds

matches the average time until the liabilities must be paid.

Q28. What is the purpose of “duration matching” in fixed income portfolio management?

Below are some of the purposes of matching duration:

- Interest Rate Risk Management: By matching the durations of assets and liabilities, an entity can hedge against interest rate risk. If interest rates change, the impact on the value of the assets should be approximately offset by a similar change in the present value of the liabilities.

- Cash Flow Management: Duration matching can ensure that the portfolio generates cash flows at the times when liabilities need to be paid.

- Funding Stability for Long-term Obligations: Duration matching is particularly important for entities like pension funds or insurance companies, which have long-term, fixed-payment obligations. By matching the duration of their investment portfolios with the duration of their liabilities, these entities can stabilize their funding status over time.

Q29. How does inflation affect fixed income securities?

Inflation

can significantly impact fixed income securities, such as bonds, in several

ways:

a)

Interest

Rates and Bond Prices:

Inflation often leads to higher interest rates, as central banks raise rates to

control rising prices. Higher interest rates can lead to lower bond prices.

This inverse relationship is a fundamental principle in fixed income investing.

When new bonds are issued at higher interest rates, existing bonds with lower

rates become less attractive, causing their market value to decrease.

b)

Investor

Sentiment and Market Dynamics:

Inflation can influence investor behavior. Concerns about inflation might drive

investors to demand higher yields for holding fixed-income securities,

especially for longer maturities, leading to a steepening of the yield curve.

c)

Coupon

Payments: Fixed

income securities typically pay fixed interest (coupon) payments. During

periods of high inflation, the real value of these payments declines, as the

fixed coupon buys less in terms of goods and services over time.

d)

Credit

Risk: Inflation

can impact the creditworthiness of issuers. For corporates, inflation can

increase operating costs and squeeze profit margins, potentially affecting

their ability to service debt. Conversely, for sovereign issuers, inflation can

sometimes increase nominal tax revenues, impacting their credit profiles

differently.

Q30. How do interest rate changes impact the prices of different bond

maturities?

Interest

rate changes have a significant impact on the prices of bonds, and this impact

varies depending on the maturity of the bond.

Interest

Rate and Bond Price

Long-Term

Bonds: They

experience greater price fluctuations with interest rate changes due to their

longer duration. For example, a rise in interest rates will typically lead to a

more substantial decline in the price of a long-term bond compared to a

short-term bond.

Short-Term

Bonds: These bonds

have shorter durations and are less affected by interest rate changes. While

they still experience an inverse relationship with interest rates, the price

movement is usually less dramatic than that of long-term bonds.

Q31. What is the role of duration in managing a bond portfolio?

a) Measuring Interest Rate Sensitivity: Duration is a measure of a bond’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. A higher duration indicates greater sensitivity, meaning the bond’s price will be more affected by interest rate changes. Portfolio managers use duration to estimate how much the price of a bond or a bond portfolio would change in response to interest rate movements.

b) Immunization Strategy: Duration is used in immunization strategies, where the goal is to hedge against interest rate risk. By matching the duration of the bond assets to the duration of the liabilities (or the investment horizon), a portfolio manager can make the value of the assets and liabilities equally sensitive to changes in interest rates, thus reducing net interest rate risk.

c) Asset-Liability Management: For institutional investors, such as pension funds or insurance companies, managing the duration of their bond portfolios is essential for aligning their assets with their future liabilities. Duration helps in ensuring that the cash flows from the bond investments are timed to meet the anticipated cash outflows.

Q32. In which all ways can financial institution manage interest rate

risk in the portfolio?

Financial

institutions use various strategies to manage interest rate risk in their

portfolios. Interest rate risk is the risk that changes in interest rates will

negatively affect the value of a financial institution’s assets or its future

cash flows. Here are some of the key ways in which this risk can be managed:

a)

Interest

Rate Swaps: These

are financial derivatives that institutions use to exchange interest rate

payments with other parties. Swaps can be used to convert fixed-rate

liabilities or assets to floating rates, or vice versa, thus managing exposure

to interest rate movements.

b)

Futures

and Options on Interest Rates:

Financial institutions use interest rate futures and options to hedge against

potential interest rate changes. These derivatives allow them to lock in

interest rates for future transactions, reducing uncertainty.

c)

Forward

Rate Agreements (FRAs):

FRAs are contracts that allow institutions to lock in an interest rate to be

applied to a future borrowing or lending transaction, helping them manage

interest rate risk on anticipated future cash flows.

d)

Cap

and Floor Agreements:

Caps and floors are types of options that set upper (cap) and lower (floor)

limits on the interest rates of a floating-rate loan or security. Caps limit

the maximum interest rate, and floors ensure a minimum rate, thus managing the

risk of adverse rate movements.

e)

Asset-Liability

Management (ALM):

This involves managing the risks arising from the mismatch between the

maturities and interest rates of assets and liabilities. By aligning the

duration of assets and liabilities, institutions can reduce the impact of

interest rate changes on their balance sheets.

f)

Duration

Gap Analysis: This

is a specific type of ALM strategy where institutions measure the gap between

the duration of assets and liabilities. A positive duration gap implies that

assets are more sensitive to interest rate changes than liabilities, and vice

versa. Adjusting the duration of either assets or liabilities can help manage

this risk.

Q33. What strategies can be employed in a rising interest rate

environment to mitigate potential losses in a fixed income portfolio?

In a

rising interest rate environment, managing a fixed income portfolio can be

challenging, as bond prices generally fall when interest rates rise. However,

there are several strategies that can be employed to mitigate potential losses:

a)

Shortening

Duration: Since

bond prices are more sensitive to interest rate changes when they have a longer

duration, shifting to bonds with shorter durations can reduce the portfolio’s

sensitivity to rising rates.

b)

Interest

Rate Hedging: Using

derivatives such as interest rate swaps, futures, and options can help hedge

against rising rates. For example, a portfolio manager might use interest rate

futures to hedge against potential losses in the bond portfolio.

c)

Floating-Rate

Notes (FRNs):

Investing in floating-rate notes, which have interest payments that reset

periodically based on prevailing rates, can be beneficial. As rates rise, the

interest payments on these bonds increase, offsetting some of the price

declines that fixed-rate bonds would experience.

d)

Diversification

Across Bond Sectors:

Diversifying the portfolio across different types of bonds, such as corporate,

government, municipal, and international bonds, can help mitigate risk since

different sectors may respond differently to rising interest rates.

e)

Inflation-Protected

Securities:

Investing in inflation-protected securities, like Treasury Inflation-Protected

Securities (TIPS) in the U.S., can be advantageous. These bonds offer

protection against inflation, which often accompanies rising interest rates.

Q34. What do you mean by term structure in Finance?

The term

“term structure” in finance, typically refers to the term structure

of interest rates, also known as the yield curve. It is a graphical

representation showing the relationship between interest rates (or yields) and

different maturities of debt securities (like bonds), all else being equal.

Here’s a breakdown of its key aspects:

Components

of the Term Structure

Maturity: The time to maturity of the debt

instruments is a crucial factor. The term structure shows how the yield changes

with the increase in the time to maturity.

Interest

Rates: These are

the yields that investors demand for investing in these securities. They are

influenced by various factors including the monetary policy, inflation

expectations, and economic conditions.

Yield

Curve: This curve

plots the yields of bonds with equal credit quality but differing maturity

dates. The most commonly analyzed yield curve is for government securities, as

they are considered risk-free.

Q35. Describe the differences between investment-grade and high-yield

(junk) bonds.

|

Parameter |

Investment Grade |

High Yield Bond |

|

Credit Rating |

These bonds are rated

as higher quality by credit rating agencies. Ratings are typically BBB- (by

Standard & Poor’s and Fitch) or Baa3 (by Moody’s) or higher. The high

rating indicates a lower risk of default. |

Also known as junk

bonds, they are rated below BBB- (S&P and Fitch) or Baa3 (Moody’s). These

lower ratings suggest a higher risk of default. |

|

Risk |

They carry a lower risk of

default. Investors consider them safer investments compared to high-yield

bonds. This lower risk is due to the stronger financial health of the

issuers, which are often stable, large corporations or government entities. |

These bonds have a higher risk of

default. They are often issued by companies with weaker financial standings,

including start-ups, companies in financially risky industries, or those with

high levels of debt. |

|

Yield |

Due to their lower

risk, these bonds typically offer lower yields. Investors accept lower

returns in exchange for the reduced risk of default and greater stability. |

To compensate for their

higher risk, these bonds offer higher yields. This makes them attractive to

investors seeking higher returns and willing to accept greater risks. |

|

Price Volatility |

Generally, exhibit less price

volatility compared to high-yield bonds, especially during periods of

economic stability. |

They can experience significant

price swings, partly because their issuers are more susceptible to economic

downturns and other adverse events. |

|

Market Sensitivity |

More sensitive to

changes in interest rates. Since they have lower yields, their prices are

more affected by interest rate movements. |

More sensitive to the

issuer’s underlying financial performance and broader economic conditions.

Their prices are more influenced by the issuer’s creditworthiness and market

sentiment. |

|

Investment Objectives |

Suitable for conservative

investors who prioritize capital preservation and steady income. |

More suited for aggressive

investors seeking higher returns and who are comfortable with higher risk,

including the potential for loss. |

|

Issuers |

Typically issued by

financially stable governments, municipalities, and corporations. |

Issued by companies or

entities that are experiencing financial difficulties, have high debt levels,

or are in industries that are more susceptible to economic downturns. |

Q36. What are different types of risks in MBS portfolio?

Mortgage-backed

securities (MBS) come with a unique set of risk factors that investors need to

consider. Understanding these risks is crucial for anyone looking to invest in

MBS. Here’s an overview of the primary risk factors associated with MBS:

a) Credit Risk

i) Non-Agency MBS: These are more susceptible to credit risk as they are not backed by government entities. The risk here is that the borrowers of the underlying mortgages may default.

ii) Agency MBS: Issued by government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) like Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, these have an implicit or explicit government guarantee, which significantly reduces credit risk.

b)

Prepayment

Risk: This risk

arises from the fact that homeowners can refinance or pay off their mortgages

early, particularly when interest rates fall. This leads to the early return of

principal to MBS investors, often at times when reinvestment rates are lower. Prepayments

can change the expected yield and the life of an MBS, making its cash flow

uncertain.

c)

Extension

Risk: The opposite

of prepayment risk, extension risk occurs when rising interest rates lead to

lower prepayment rates. This can extend the duration of MBS, causing investors

to face lower yields for a longer period than initially anticipated.

d)

Interest

Rate Risk: MBS are

sensitive to changes in interest rates. When rates rise, the value of existing

MBS tends to fall. This is a standard risk for most fixed-income securities. Interest

rate movements also influence prepayment and extension risks.

e)

Liquidity

Risk: While agency

MBS are generally liquid, non-agency MBS can be less so. The secondary market

for non-agency MBS can be less active, making it harder to buy or sell these

securities without affecting their price.

f)

Economic

and Market Risks: The

broader economic environment, including the health of the real estate market,

impacts the performance of MBS. Economic downturns, changes in housing prices,

and unemployment rates can affect mortgage defaults and prepayments.

Q37. What are municipal bonds?

Municipal

bonds, commonly referred to as “munis,” are debt securities issued by

states, cities, counties, and other governmental entities in the United States

to finance public projects. These bonds are a critical tool for local and state

governments to raise funds for various purposes, including the construction of

schools, highways, hospitals, sewer systems, and other public infrastructure

projects.

Q38. What is the difference between a senior bond and a subordinated

bond?

Senior

bonds and subordinated bonds are two types of debt instruments issued by

companies, but they differ primarily in their priority in the event of a

bankruptcy or liquidation.

|

Parameter |

Senior Bond |

Subordinated Bond |

|

Priority |

Senior bonds are higher

in the repayment hierarchy. In the event of a company’s bankruptcy or

liquidation, holders of senior bonds are paid before other creditors and

bondholders. |

Subordinated bonds are

lower in priority during bankruptcy or liquidation. They are repaid after

senior bondholders and other priority debts have been settled. |

|

Risk |

Because of their priority status,

senior bonds are generally considered to be less risky compared to

subordinated bonds. |

This lower priority means that

subordinated bonds carry a higher risk of default. In case of financial

distress, there might not be sufficient assets left to fully repay these

bondholders. |

|

Interest Rates |

The interest rates on

senior bonds are usually lower than those on subordinated bonds, reflecting

the lower risk. |

To compensate for the

higher risk, subordinated bonds typically offer higher interest rates

compared to senior bonds. |

|

Investor Appeal |

Senior bonds are often preferred

by more risk-averse investors who prioritize the security of their principal

and interest payments. |

These bonds may be more

attractive to investors seeking higher yields and who are willing to accept a

greater level of risk. |

Q39. What are the key characteristics of mortgage-backed securities

(MBS)?

MBS are a

type of asset-backed security that is secured by a collection, or

“pool”, of mortgages. Investors in MBS receive periodic payments

similar to bond coupon payments.

|

Parameter |

Investment Grade |

|

Underlying Asset |

MBS are backed by

mortgage loans. The mortgages pooled in an MBS can be residential

(residential MBS or RMBS) or commercial properties (commercial MBS or CMBS). |

|

Types |

Pass-Through Securities: The most common type of MBS,

where the principal and interest payments from the underlying mortgage loans

are passed through to investors.

Collateralized Mortgage

Obligations (CMOs):

These are more complex and are divided into different tranches that have

varying levels of risk, maturity, and interest rates. |

|

Issuer |

Government Agencies: Such as Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae,

and Freddie Mac. They issue agency MBS, which have a guarantee against

default.

Private

Institutions:

Such as banks and other financial institutions, issue non-agency MBS, which

do not have a government guarantee and typically carry higher risk. |

|

Returns and Yields |

MBS typically offer higher yields

than U.S. Treasury securities, compensating for their higher risk levels,

especially for non-agency MBS. |

|

Liquidity |

Agency MBS are

generally quite liquid. Non-agency MBS can be less liquid, depending on the

market conditions and the specifics of the security. |

Q40. What is a Mortgage-Backed Security (MBS) and how does it work?

A Mortgage-Backed Security (MBS) is a type of financial instrument that is secured by a pool of mortgages. Essentially, it represents an investment in a group of home loans. Here’s how it works:

Creation of MBS:

- Pooling Mortgages: It starts with financial institutions, like banks, which originate mortgages. These mortgages are then grouped together to form a large pool. The size and characteristics of the mortgages in the pool can vary.

- Selling to an Issuer: The bank then sells this pool of mortgages to a government agency or investment bank. The most common issuers of MBS are government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) like Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae.

Securitization Process:

- Transformation into Securities: The issuer then turns these pools of mortgages into tradable securities. Each MBS represents a claim on the payments made by the borrowers of the pooled mortgages.

- Tranching: In some cases, these pools are divided into different sections or “tranches,” each with a different level of risk and return, based on factors like the maturity of the loans and the creditworthiness of the borrowers.

Investment:

- Buying MBS: Investors buy these securities for a variety of reasons. Some are attracted by the regular income stream from the mortgage payments, while others might be interested in the relatively low-risk nature of certain tranches.

- Payments to Investors: As homeowners in the pool make their mortgage payments, this money is passed through to the holders of the MBS, typically on a monthly basis. These payments include both interest and principal repayments.

Q41. What are risk associated with Mortgage-Backed Security (MBS)?

The major

risks associated with Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) are primarily related to

credit, interest rates, prepayments, and liquidity. Understanding these risks

is crucial for investors and financial professionals dealing with MBS. Here’s a

breakdown of each:

·

Credit

Risk: This is the

risk that borrowers within the pool of mortgages will default on their loan

payments. While this risk is somewhat mitigated in agency MBS (those issued by

government-sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae)

due to government backing, it remains a significant concern in non-agency MBS.

·

Interest

Rate Risk: MBS are

sensitive to changes in interest rates. When rates rise, the value of existing

MBS tends to fall, similar to traditional bonds.

·

Reinvestment

Risk: When rates

fall, homeowners may refinance their mortgages. This leads to early repayment

of the principal, forcing investors to reinvest at lower, less favorable rates.

·

Prepayment

Risk: One of the

unique features of MBS is the uncertainty regarding the timing of cash flows,

as homeowners can refinance or pay off their mortgages early. This

unpredictability can make it challenging to determine the actual yield or

duration of an MBS.

·

Extension

Risk: When

interest rates rise, the likelihood of prepayment decreases, which can extend

the duration of an MBS. This means that investors may have to wait longer than

expected to receive their principal, exposing them to prolonged interest rate

risk.

·

Liquidity

Risk: Some MBS,

especially non-agency and certain complex structured products, may face

liquidity issues, making it difficult to buy or sell them quickly without

impacting the price. Also, the market for certain types of MBS can be limited,

further exacerbating liquidity concerns.

·

Model

Risk: The

valuation and risk assessment of MBS often rely on complex models. Inaccuracies

in these models can lead to mispricing or misunderstanding of risk levels.

·

Systematic

Risk: MBS are

influenced by broader economic factors such as housing market conditions,

unemployment rates, and overall economic health, which can affect the

performance of these securities.

Q42. What are the different types of MBS?

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) come in various types, each with its own characteristics and structures. The main types include:

Fixed-Rate MBS:

Fixed-Rate MBS are backed by fixed-rate mortgages, where the interest rate remains constant throughout the term of the mortgage. These securities provide investors with a predictable income stream, as the interest payments do not change over time. They are susceptible to interest rate risk, as their value can decrease when market interest rates rise.

Adjustable-Rate Mortgage (ARM) Backed Securities:

These are MBS backed by pools of adjustable-rate mortgages. The interest payments to investors can vary over time, as they are linked to the interest rate fluctuations of the underlying ARMs.

Agency MBS:

These are issued by government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) like Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. Agency MBS typically have a guarantee of principal and interest payment, which significantly reduces credit risk.

Non-Agency MBS:

Issued by private entities like financial institutions, these MBS do not have the backing of a government agency. They usually carry higher risk compared to agency MBS and often cater to investors looking for higher yields.

Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS):

Unlike residential MBS, CMBS are backed by commercial mortgages on properties like office buildings, retail space, or hotels. The structure can be similar to residential MBS, but the underlying asset and associated risks differ due to the nature of commercial property loans.

Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities (RMBS):

RMBS are backed by mortgages on residential properties. These can be loans for homeowners (single-family homes) or multi-family dwellings. The mortgages in an RMBS can be a mix of different types, including both fixed-rate and adjustable-rate mortgages. The risk profile of an RMBS largely depends on the creditworthiness of the borrowers and the types of residential loans included in the pool.

Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS):

Unlike residential MBS, CMBS are backed by commercial mortgages on properties like office buildings, retail space, or hotels. The structure can be similar to residential MBS, but the underlying asset and associated risks differ due to the nature of commercial property loans.

Pass-Through Securities:

These are the simplest form of MBS. In a pass-through, the principal and interest payments from the underlying pool of mortgages are passed directly to investors. They typically have a monthly payout and are subject to prepayment risk.

Q43. What is tranching in Mortgage-Backed Securities, and why is it important?

Tranching in Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) is a process that divides a large pool of mortgage loans into smaller, distinct segments or “tranches,” each with its own unique characteristics and risks. This segmentation is crucial for catering to a diverse range of investors with varying risk appetites and investment objectives.

Characteristics of Different Tranches:

- Senior Tranches: These have the highest priority and are usually the least risky, as they are the first to receive payments from the mortgage pool. They typically have lower yields compared to other tranches.

- Mezzanine Tranches: These fall in the middle in terms of payment priority and risk. They offer higher yields than senior tranches but come with greater risk.

- Equity/Junior Tranches: These are the last to receive payments and bear the highest risk, including the risk of default. Consequently, they offer the highest potential yields.

Q44. Can you explain what Option-Adjusted Spread (OAS) is and how it

is used in fixed-income securities analysis?

OAS is

essentially a spread measure that accounts for the potential impact of embedded

options on the bond’s yield. It reflects the extra yield (over a risk-free

rate) an investor can expect to earn, adjusted for the option risk.

Usage in MBS and Other Securities:

- In the context of MBS, which often include prepayment options, OAS is crucial for understanding the yield in relation to prepayment risk.

- For callable bonds, OAS adjusts for the risk that the issuer may call the bond back before maturity.

- For putable bonds, it adjusts for the holder’s option to sell the bond back to the issuer.

Q45. How does OAS differ from Z-spread, and why is this distinction

important?

Option-Adjusted

Spread (OAS) and Z-spread (Zero-volatility spread) are both measures used in

fixed-income securities analysis, but they serve different purposes and are

used in different contexts

Z-spread is a constant spread that is added

to each point of the zero-coupon Treasury yield curve to make the present value

of a bond’s cash flows equal to its market price. It’s used to measure the

spread that investors can expect to earn over the entire Treasury yield curve,

not just a single point or maturity. Z-spread is commonly used for option-free

bonds. It assumes that the cash flows of the bond are not affected by interest

rate changes.

OAS is a spread measure that adjusts the Z-spread for the impact of embedded options in a bond. It represents the yield spread relative to a risk-free rate, considering the likelihood of the options being exercised. OAS provides a more accurate measure of a bond’s yield spread by accounting for the option risk, which can alter cash flows. OAS is particularly useful for bonds with embedded options, such as callable, putable bonds, or Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS).